“You’ll Be Crying in a Minute,” remains one of my favorite pieces. The story was written at a time when motherhood was out of fashion amid all the excitement over women entering and succeeding in the workplace. Those of us who were pioneering working moms got plenty of encouragement for our career advancement, but no acknowledgment for the incredible emotional labor involved in parenting. Although I had a demanding magazine editing job, I always knew that I went to work to rest.

By Ronni Sandroff | 1996 | Mothers: Twenty Stories of Contemporary Motherhood | North Point Press | Originally published in Redbook Magazine

With other people suffering so much anguish, it doesn’t seem fair that the wings of trouble keep passing my family by. The four of us sit at dinner, evening after summer evening, without so much as a cold among us. Our house is not in a flood area, on an earthquake ledge, or near a combat zone: none of us is on methadone, taking fertility pills, or under indictment for a crime. I don’t work at a dead-end job. I have nothing to worry about.

And yet I’m as busy with worry as a woman trying to knit a sweater before her child can outgrow it. Worry knots my fingers; it rubs them raw. I tally all neighborhood suicides and accidents as if I were a bookmaker keeping odds on survival.

I wasn’t always this way. I was so busy tugging at the perimeters of our lives to make them take a shape that pleased me, so busy amending, revising, and adjusting our routines, that I had no idea I’d be filled with dread as soon as everything was right. I was raised to be heroic in times of crisis—to get the children to the hospital emergency room first and faint afterward. I was never taught to handle satisfaction, admiration, praise.

Cara set next to me in the company cafeteria today, and after a comment about hard pears and soggy bread she asked the usual question: “How do you manage both children and a job?”

The next time I give a serious answer to that question, I thought, I’ll have to be paid for it. “Badly—i do it all badly,” I said and tried to turn the talk to the one current film my husband, Gary, and I have managed to see.

“You don’t do it badly,” Cara said. “You just got a promotion—after only three months—and your son and daughter are beautiful.”

I put my sandwich down on its paper plate. Pastrami is hard to chew anyway, but it’s inedible when my mouth is full of motherhood. I tried to be patient with Cara. I admire her long, limp skirts and eyelet blouses, her permanent way, her salad lunches.

“I can’t imagine having kids,” Cara said, her fork darting for an olive. “And I’m almost thirty-three. Neil and I haven’t much time to decide.”

I batted her a few reasons for not having children. I exaggerated Sarah’s aggressiveness (“Almost ever day I get a call from the mother of some child she’s bloodied”) and Kane’s prying (“I think he listens at the door when we make love.”) I told her of the spring of the great chicken-pox epidemic; about going home from our quiet office to find that no one’s put the potatoes in to bake; that Kane needs help with math and, horror of horrors, Sarah has an art project due the next day, and there’s not a shoe box in the house.

Care kept the same bemused expression on her face no matter what I said. “Does it hurt a lot, having a baby?”

“Yes. It hurts a lot, and it keeps on hurting,” I said meanly. Damn her narrow hips and graceful arms. Damn her questions. I don’t want to be forced to make up explanations for what I do with passing, by instinct, blindly. If I’d thought about it as much as she thinks about it, I might have talked myself out of having children too.

The lunch with Cara leaves me shaken. It’s bad luck to hear someone say out loud, as Cara did, that I’ve had more than my share of goodies from life. Something could go wrong at any minute. After I began to work, whole afternoons would go by when I’d forget to worry about the children. I’d try to make it up to them when I got home.

As I drive down our street, I see a white truck with a revolving red light parked near our house. I know it isn’t an ambulance. I know it’s not parked in front of our house. But what if it were? During the one-block drive, I picture both children laid out on stretchers with burns covering ninety per cent of their bodies. There is no place I can touch them without causing pain. Their lungs are scorched; they cry in silence; their eyeballs melt.

The white truck belongs to the electric company. Men are digging in the asphalt in the middle of the street. But even the sight of my family sprawled in front of the huge TV set can’t stop me from completing imagined funeral arrangements for them all. There are rows of sobbing school friends; a grandmother faints at the grave.

The baked potatoes are in the oven. The table is set. The children make a salad while I broil the chops, and although we keep bumping into each other in the small kitchen and green cucumber peels slap the floor, dinner is on the table in twenty minutes.

I sit down in my chair, put my face in my hands, and wait until the anxiety I have felt since lunch can ebb. When I look up, my family is staring at me.

“Hard day?” Gary asks.

“No, not particularly.”

“You look tired,” Sarah says.

Kane wiggles his eyebrows at me, his blue eyes popping in his latest imitation of a TV commercial.

I put sour cream on my baked potato and pour juice for Kane and Sarah. I pass Gary the chops. I tell Sarah not to sit on her feet. I ask Kane to stop wiggling his eyebrows.

The children eat quickly and leave the table before I’ve finished my salad. They go into Kane’s small room, right off the dining alcove, and close the door.

“Remember Kalligan, the man who owned the liquor store on Ocean Avenue?” Gary asks.

I brace myself for a tale of trouble. “What happened to him? Was he hit by a truck? Did he leap from a burning building? Was he arrested for bribing a state liquor inspector?”

“I don’t make these things up.”

“You always bring home terrible news. What happened?”

“I’m not going to tell you if you’re going to take it personally.” But he cannot hold out. “The poor man had a heart attack. He dropped dead in his store. A customer found him.”

“That’s too bad. I liked him.” when will other people say such things about us? Too bad about Sarah and Kane. Too bad about Gary’s accident. Too bad about Sheila’s nervous breakdown—did you hear? They’re giving her shock treatments. She sobs all day, mourning the future victims of a nuclear war.”

I start to laugh, and Gary gives me one of his looks—jaw rigid, eyes cold as aluminum—warning me back to sanity.

“It strikes me as funny sometimes,” I say. I drop a tomato from my fork as I try to explain. “All the world’s problems loom over us like monsters in a nightmare, but we just keep chasing after our personal happiness. The human race is so dumb and funny, and cute.”

Gary smiles tentatively. “Cute, huh?”

“Yes, cut. Especially you.”

We hear thumps and squeals from Kane’s room—the hysterical laughter of a small boy being tickled by his older sister, tickled until his sides ache and he can’t break and wants to put a sneaker in her ribs.

“They’ll be crying in a minute,” I say to Gary. He nods. I rise to rap on the closed door. “Keep the noise down.”

“Okay,” they say, still giggling. I can hear the thumps of pillows being thrown across the room. My mother’s word is struggling to be said: You’ll be crying in a minute. At the most ecstatic moments of my childhood, I heard that.

The laughter turns to shrieks. I try to open Kane’s door, but it is blocked by their bodies piled in a jumble of limbs. I squeeze through the small opening.

“We’re having fun,” Sarah calls.

Kane peers out from beneath her chest and wiggles his eyebrows.

I know someone will get hurt. It’s dangerous to feel so good. Too much happiness attracts the evil eye of disaster. Or is it dwelling on disaster than brings it on? It’s hard to know which superstition to believe. The children, frozen in mid-tickle, start at me. I hold myself tight, refusing to contaminate them with my fears.

“I didn’t’ have the heart to stop them,” I tel Gary, falling back into my chair. “Their idea of fun is to tickle and scream until they turn blue.”

Gary touches my hand. “They’re both at a good age. Not babies anymore but too young to have a driver’s license. Did you hear what happened to the oldest Kenmore boy?”

I smile at him. He’s looking awfully good with his face tanned. I stop wondering why some slim-hipped secretary doesn’t walk off with him; I’ve fed the snapping jaws of worry enough today.

And I resist asking what happened to the Kenmore boy. Our children are at a good age if you can stand the noise, and we’re at a good age too. We’ll all be over the edge soon, but meanwhile, in the sliver of time before the sobbing starts, I let the dangerous feelings of contentment fall like a light shawl on my shoulder and slip off my watch so I won’t be able to count the minutes until the eleven o’clock news.

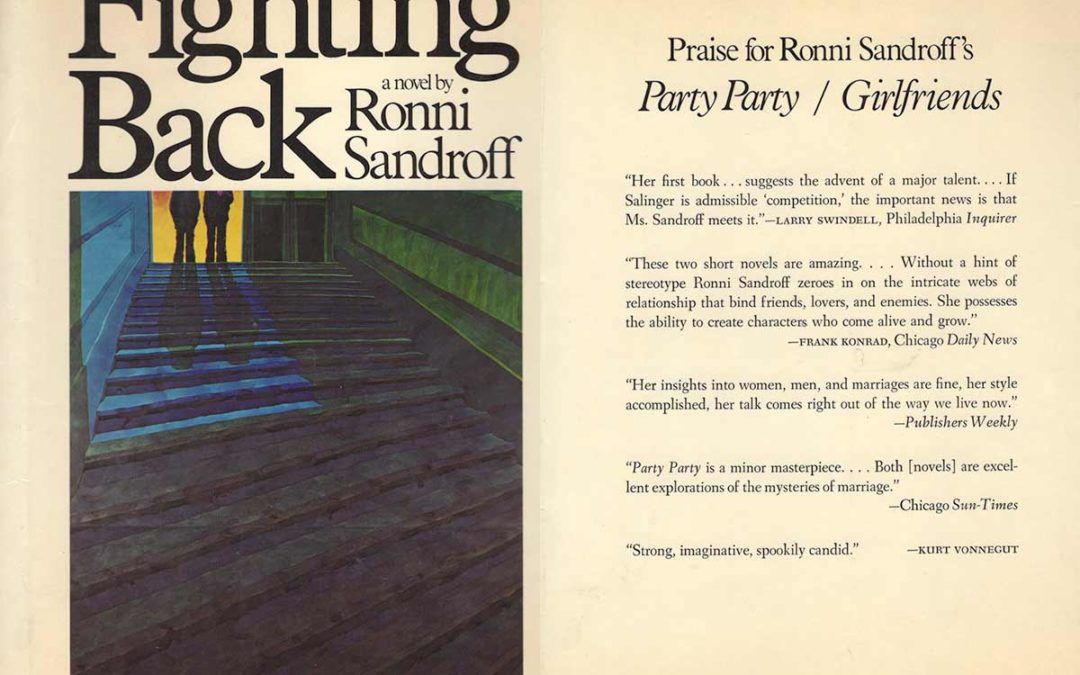

Three years after her literary debut, praised by Kurt Vonnegut as “strong, imaginative, spookily candid,” Ronni Sandroff gives us a powerful new novel. In Fighting Back, she takes us into the life, the feelings, the fears of a young woman entangled in—and trying desperately to get out of—a religious organization that has a total and terrifying control over its members.

The Church of All. Jeanie knew them well—the smiling “Allees” who stood on street corners and hooked for lost souls…their seductive leader who made evil seem holy…her husband, “Brainstorm,” wrapped up in his mind control program for the organization. She knew them—and she was going to expose them and their government connections. If she could stay alive long enough to do it.

“First rate psychological thriller…Timely as today’s headlines.” —Mademoiselle

Click here to purchase the book.

Party Party

“At once serious and light-handed, these novels mark an auspicious debut for a natural—a brilliant—young writer.”

Danny Yoder, graduate student and deserted husband of Allegra, talks—and drinks—through the long night of his wife’s disappearance, waiting for her to (perhaps) come home. He talks in his own voice (“I’m the bastard of the piece. The bleak truth is that tonight would have been boring if Allegra came home.”) soon he is speaking in a carousel of vices conjured from memory or fancy, keeping him company while he keeps his panic at bay.

Here, captured with a rare combination of ventriloquial mimicry and a knowing tenderness, is the emotional whirligig that marriage (and the suspense of separation) can engender.

Girlfriends

The friends. Isabel Schneider: 29, “fulfilled homemaker,” mother of three, the perfect graduate-student wife of Brian—swims in the morning, works in a daycare center, knows exactly how to spend the money her in-laws send to make a cozy home and refuge for her endlessly aspiring scholar-husband. And Zimmie Alp: 21, a born blues singer and composer, lover of Chopper—jock and blooming revolutionary—and pregnant with his child, believer in Free Relationships—no contracts. Zimmie has been (just temporarily) abandoned by Chopper. Isabel has just learned that her husband is unfaithful.

Through the days of their closeness, through the chinks in their immense difference, through talk Isabel starts to know who she is and Zimmie opens up to the aches that survive all her resolve never to be possessive. In their exchange of nerves, in the self-confrontation each inspires in the other, each moves away from a hidden scaredness towards the capacity for real and risky decision.

Click Here to buy the book

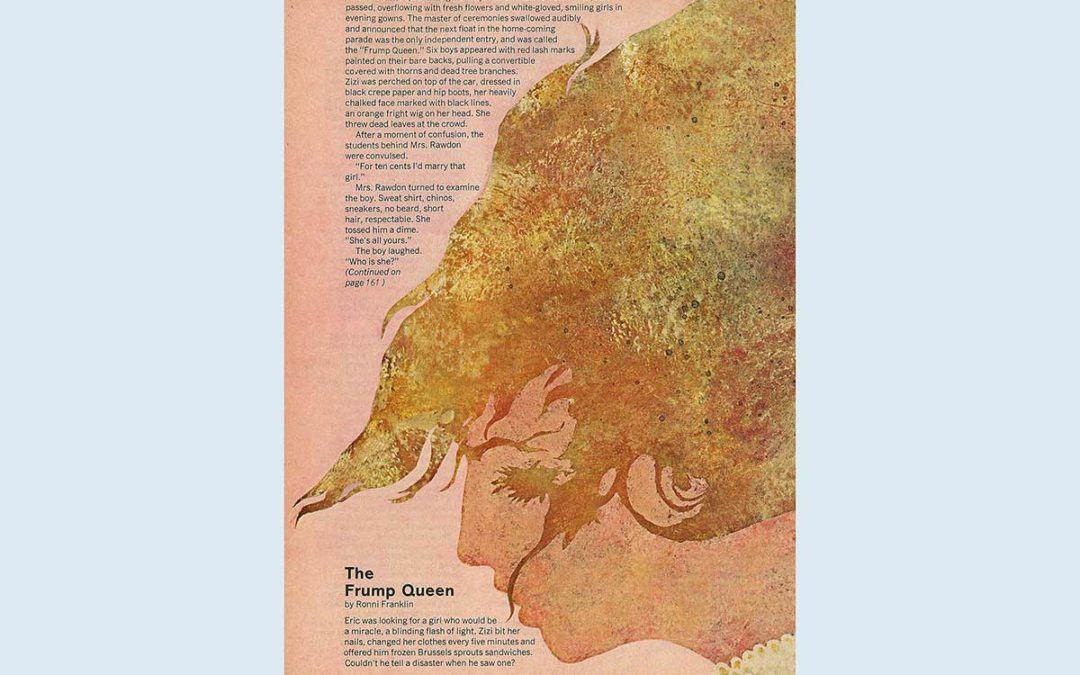

By Ronni Sandroff | Oct. 1968 | Redbook Magazine

Twelve floats, representing the major sororities and fraternities, had passed, overflowing with fresh flowers and white-gloved, smiling girls in evening gowns. The master of ceremonies swallowed audibly and announced that the next float in the home-coming parade was the only independent entry, and was called the “Frump Queen.”

Six boys appeared with red lash marks painted on their bare backs, pulling a convertible covered with thorns and dead tree branches. Zizi was perched on top of the car, dressed in black crepe paper and hip boots, her heavily chalked face marked with black lines, an orange fright wig on her head. She threw dead leaves at the crowd.

After a moment of confusion, the students behind Mrs. Rawdon were convulsed.“For ten cents I’d marry that girl.”

Mrs. Rawdon turned to examine the boy. Sweat shirt, chinos, sneakers, no beard, short hair, respectable… She tossed him a dime. “She’s all yours.”

The boy laughed. “Who is she?”

“My darling daughter. Last summer I made a drastic mistake. I said ‘Zizi isn’t it remarkable that you’ve got through three years of college without being queen of anything?’ As soon as I saw the gleam in her orange eyes, I knew something like this would happen.”

“Orange eyes?” The Frump Queen moved out of sight, and a group of Shriners in midget cars and clown costumes spun in circles down the street.

Mrs. Rawdon sighed. “My daughter has only one redeeming quality to her credit. She can make people laugh.”

“I’d really like to meet her. It must take a lot of courage to pull a stunt like that. In this town, nobody makes fun of home-coming.”

“For anyone else, it would take courage. For Zizi, it’s just a matter of lack of self-control.”

They turned to the next float, on which a valentine of pink and white flowers formed a swing for Miss Perfect Profile. Mrs. Rawdon poked the boy. “Zizi has a better profile than that. But it’s beneath her dignity to enter a con· test. She has to pull some crazy . . . What’s your name?”

“Eric. Eric Wilmot.”

“What’s your major? Don’t mind me -I’m just doing a little market research.”

“I’m between majors. I used to be in economics, but I got bored. I’m thinking of switching to philosophy.”

“Philosophy’s a terrific major,” Mrs. Rawdon said thoughtfully. “There are lots of opportunities in philosophy nowadays. When you graduate, you can join one of the big philosophy corporations, or open a little philosophy shop, or the government . .. Now, the government has a serious philosopher shortage.”

Eric laughed. “You’re very funny.”

“How nice of you to notice.”

“If I’ve passed the test, I’d like to meet your daughter.”

“Well, actually I was in the market for a third-year medical student, but . . . Do you have a girl friend?”

“I’m between fiancees. I tend to fall in love at first sight and out of love on second sight.”

“Between majors, between fiancees. Let me guess. Are you trying to find yourself? Or lose yourself?·’

“No, I’m waiting for something to interrupt my life-a sign, a miracle, a disaster, a blinding flash of light that will transform a nervous college kid into a decisive, ambitious man of the world.”

Mrs. Rawdon smiled. “Come-I’ll introduce you to my disaster.”

They weaved through the parking lot where the floats were disassembling. They spotted the Frump Queen float immediately; it was the only one the children were ignoring.

“Mother! Didn’t you love me? Zizi ran toward them, crepe paper trailing.

“You were gorgeous. You brought honor to your school and family. Zizi, this is Eric Wilmot.”

“You finally took a lover!”

“Eric is between fiancees. I bought him for you for a dime. Good night.”

Zizi walked around him. “Not bad· looking. What are you in-medicine, engineering or law? Wait, mother, I’ll walk you to the bus:·

“In that outfit?·’

The three of them fought through the dispersing crowd. Eric tried to study Zizi’ face in the street lights, but the mask and make up was too thick to see through. At the bus station they squeezed Mrs. Rawdon in between a tuba player and a high school cheerleader and waited until the bus drove off.

“Where did she pick you up?” Zizi demanded.

“She walked through the crowd, asking if anyone would marry her daughter. I said sure.” Eric was aware that everyone in the crowded terminal was staring at her. ”’My scooter’s parked around here. I’ll take you to the dorm to change.”

She grinned through the make up. “I have my own apartment. Special permission from a wonderful mother and a badgered dean:’

As soon as they reached her apartment, Zizi vanished into the bedroom, leaving Eric to wander around the bizarre living room. The flat looked like a circus. Nine-foot posters of circus animals and artists covered the bright green, red and yellow walls. Colored lights revolved on a carrousel-shaped lamp. There was no place to sit except on pillows on the floor. Looking up, Eric discovered a deep blue ceiling studded with plastic stars. He waited, gingerly touching the decorations, until Zizi reappeared, wearing a full length velvet hostess dress, her face free of make-up. She was a little too short, too round, for Eric’s taste, but her face was fashion-model perfect-and lively as well, changing expression with dizzying animation.

“Are you hungry?” she asked.

Eric -followed her into the tiny kitchen, where box tops and canned-soup labels were pasted on the walls. She opened the refrigerator.

“I have cola, frozen Brussels sprouts, peanut butter and one lemon. How about a Brussels sprouts sandwich?’

“Come on-I’ll buy you a pizza.”

“You don-t have to.” She sat next to him at the kitchen table. “I don’t know how my mother drummed you into this. She’s afraid that if I leave college without getting married, I’ll run off to New· York and lead a life of sin and die in the gutter.”

“What do you want to be after you graduate?”‘

“Ecstatically happy.”

Eric was unexpectedly moved.”I hope you make it.”

“Well, I work very hard at it. And what do you want to be when you grow up?”

“Brilliant:·

She smiled, and Eric was fascinated by the movement of her cheeks from con· cave to convex, her expression from deadly serious to highly amused .. He.. moved

to the phone. “I’ll call for a pIzza:·

Zizi charged back into the bedroom and reappeared almost immediately in a red-and-white·checked dress. “My Italian pizza outfit. I’m majoring in drama, could you tell?”

did notice some kind of costume fixation.’·

“What do you want to be brilliant at?”

“I don’t know yet. I’ll join either the. Peace Corps or IBM.”

“Trying to find yourself, eh?”

“That’s what your mother said:”

Zizi laughed and wriggled in her chair. “I would like to fall in love with you simply because my mother picked you. I complained to her that I knew millions of people but had no boy friend, and she said, ·‘I bet I could find a mate for you in two hours.’ She has the ridiculous idea that I’m great, but no one has the sense to appreciate me.”

Eric tilted back in his chair, trying to appreciate her. She was exhausting to watch. Her body was always in motion she played with a cigarette, tinkled glasses, tapped her foot. But Eric found her relief from the soft-spoken sorority girl.’ who never said anything unexpected.

“I liked what you did tonight:’ he said. “Your float satirized all those little lovelies.”

Zizi shrugged. “Actually I love home-coming. Frump Queen was just a joke. I thought it would add to the parade: ‘

“Oh, it did. I was ready to leave and go back to my homework, but the Frump Queen turned out to be more interesting than Hegel.”

Zizi cut her finger as she sliced a lemon for the colas, screamed in mock horror and wound a huge bandage around the little cut. Eric applauded. “I’m better off stage than on,” she said. “Perhaps you saw my show-stopping performance in the crowd scene of Romeo and ]Juliet.“

“I hate the theater,” Eric said, bracing himself for her reaction. She opened the door for the pizza man.

“I hate Hegel.” They ate the pizza silently. Eric wondered why he was wasting his time here, then shook off the thought. He was getting too impatient with women lately. If they didn’t immediately strike him as a prospective wife, he wasn’t interested in simply enjoying them.

“What do you have against the theater?” Zizi demanded after the pizza was finished.

“I just said that to goad you on to new heights of wit.“

Zizi nodded dully. “People generally do that. I’m a very difficult person to be sincere with. Boy, am I feeling let down now. For three weeks I spent every moment designing that float, and it didn‘t disrupt the face of the universe after all. No magnificent changes have been wrought in me. I hoped for a miracle.”

Eric shook the ice in his glass, resorting to nervous motion himself now that she was still. “I feel that way all the time. I really expect something spectacular to happen to me any moment, something that will change my life, the answer to all my problems. Getting married did that for my brother. As soon as he could take his mind off looking for girls and sex, he was free to solve all the minor problems like what he wanted to be and what he believed in and where he wanted to live.”

“I think all my problems would be solved if I just had a date Saturday night.” Zizi sprang up and put the glasses in the sink.

“You’d better go now. It‘s one o’clock.”

“Don’t tell me the dorm mothers check up here.“

“It’s a deal with my mother and the dean. I’m on my honor to keep good hours. And my honor“–she waved her bandaged finger at him-“is almost as important to me as clothes.”

Eric was trying to make up his mind whether to ask her out when she solved the problem at the doorway. “Tomorrow’s my birthday. Want to come to my party?“

“Sure. How old will you be?” She counted quickly on her fingers. “Twenty years and three months. Don‘t forget to bring a present.”

Eric spent most of Saturday after· noon trying to find a birthday present for her. It had to be inexpensive–he was broke-and incredibly funny. He finally ended buying a tube of pick–up-sticks at the dime store. His image of Zizi reminded him of one he had of his kid sister trying to master pick-up-sticks, frustrated by her clumsy fingers and bitten nails. Did Zizi bite her nails? He couldn‘t remember. He felt very happy walking back to his apartment, rattling the tube of sticks. After almost four years in the same college town, with the same friends and the same routine of studying, worrying about the draft, working in the library and taking polite young ladies to second-rate movies, he was enjoying Zizi‘s bizarre interruption of his life. He warned himself not to get too excited. Thinking about her was pleasant, but the kindest critic had to notice her instability. She was too turned on, too clever, and then too unexpectedly solemn, to fit into his life.

Eric heard the party as soon as he drove up to Zizi‘s block. The record player, accompanied by live bongos and a guitar, echoed into the street. “Come on in–it‘s the maid‘s day off,” a male voice called in answer to his tentative knock. Eric stood in the doorway, amazed that nearly thirty students had crowded into the small room. He couldn‘t find Zizi anywhere amid the dancing couples, so he threw his coat and the present on the bed and found a vacant pillow to sit on. When the dancers stopped, waiting for the next record to drop, he noticed a huge, gaily wrapped carton in the center of the room. A moment after he saw it. the top flew open and Zizi popped out in a short, pink flapper dress with beads down to her ankles. “Welcome to my party!” she cried.

Eric seemed to be the only one surprised. Someone quickly put on a 1920s record and a boy led Zizi into a wild Charleston. The crowd pressed against the walls to make room for their dance. Zizi’s low·cut mini dress seemed about to falloff on the next swing of her leg, and the long beads swung crazily. When the dance was finished her partner was exhausted, but Zizi was not. She bounced around greeting everyone, brushing away the boys who tried to slip the slim dress straps off her shoulders. It suddenly seemed to Eric that everyone was making fun of her. She was so vulnerable in her little dress. One quick, cruel motion ·could strip it off her. He worked his way out of the corner toward her. “That was quite an entrance,” he said.

“I didn‘t think you’d come. What‘s a nice guy like you doing in a place like this?” She was smiling, but her smile seemed applied with her make· up. Eric was fascinated by her long, false eyelashes and even, pink fingernails. The music started again. “Dance with me;‘ she said. “No–I could never keep up.” She smiled. “Well, then, maybe I’d better slow down.”

She put on a soft, slow dance, and Eric danced with her for a moment, then led her into the bedroom. “I bought you a birthday present.” He gave her the tube, and she squealed.

“Perfect! How did you know I love them? Stay after everyone leaves and we’ll play.” For a while Eric enjoyed watching the spectacle of the wildly dressed, dancing girls and boys, but soon his head hurt from the pulsating lights and music. Zizi stayed away from him, going about the room to refill drinks and wisecrack with her guests. There would be a burst of laughter from every group when she arrived, and, it seemed to Eric, a quieter laughter after she left. The party was at such a high pitch that he felt some act of high drama-violence or humiliation, with Zizi a its victim-had to bring it to a climax. He went quietly to the bedroom to get his coat. He didn’t want to witness the event. And he was sure by now that Zizi was not the interruption in his own life that he longed for.Zizi caught him at the door and dramatically barred the way with her body.

“You’re not leaving!”

“I have a headache. But I had a very nice time … …

She pressed his hands. “I’ll get rid of them.” She snapped off the record player, clapped her hands and cried, ”I’m starving! Let’s have a race to Hank’s Roadside Inn! Everyone into your cars!”

The guests cheered, and the room emptied with amazing speed. When they had all gone, Zizi leaned against the door, laughing. “Well, take off your coat! I’m going to change into my pick-up -ticks playing outfit.”

Eric collected the glasses and empty beer cans while he waited, enjoying the silence. Zizi emerged from the bedroom in a pair of shredding dungarees, a large sweater, and a baseball cap. Eric grinned at her.

“I’m sorry I made you call off your party.”

“I invited you to a party, so I had to produce one. But you didn’t like the party, so poof! Party’s gone.”

She threw the pick-up-sticks on the floor and Eric grabbed her hand. “Where are your pink nails?”

“They were phony. I took them off.”

He laughed. “You bite your nails?”

“Of course. Very tasty.” She licked her lips, and Eric leaned over and kissed her quickly. “Now, listen!” She shook her head. “If we’re going to start that stuff, I’ll have to put on my seduction outfit.”

“If you change your clothes once more, I”m leaving’,” Eric said. ”I’m trying to find out if you’re the girl of my dreams and you keep changing into a million different girls.”

“Of a million different dreams. I’m sure that someday someone will see me in an outfit that bowl him over and fall, instantly in love with me, and I’ll change my whole wardrobe to conform to the right image.”

“I’d like to see you without any clothes on,” Eric said. “Oh, I didn’t mean-or did I?” He laughed, but she was very quiet, studying the pick-up-sticks formation.

“You rattle me. You rattle the very core of my peaceful existence. I’m usually very cool with women-smooth, relaxed, seductive.”

“A regular playboy.” She carefully lifted a stick. “And I could never play these tete-a-tete scenes. I need a huge supporting cast, music, crowds, lights. So you rattle me a bit too, you see.” She tried to remove a stick from the top of the pile and jiggled several others. “Damn! What self-respecting man is going to fall in love with a girl who can’t play pick-up-sticks?” She beat her fist on the floor until Eric caught it.

“Let’s take a quiet walk in the cemetery,” he said. “And don’t put on your shroud!”

“I’ve got to master this pick-up-sticks thing.” “Don’t. Let’s get out of this crazy room.”

“The decor of a home reflects the personality of its owner,” she said, then turned on him suddenly. “You just sit around waiting for some great thing to happen to you. I make them happen.” “I think you work too hard at it,” he said, “or in the wrong ways. But you’re right about me. Why did you ask me to come tonight, anyway?” “You’re cute. My mother liked you. And I’m ridiculously lonely and don’t believe in sitting around waiting for the phone to ring. So you’d better get out right now:’

She brought him his coat and held the door open. “I’m not leaving until I get my chance at pick-up-sticks,” he said, sitting down on the floor.

She tossed his coat beside him and kicked over the sticks. He laughed, pleased with his power to annoy her.

“Stop pacing around like an over· wrought maiden in a melodrama.”

She tapped her foot. “You’re so arrogant. You really get on my nerves!”

He gathered up the scattered sticks, threw them out again and worked carefully and methodically to remove them one by one. Despite herself, Zizi became absorbed in watching him, and shouted triumphantly when he eventually shook the whole pile, and it was her turn.

When they had finished the game, he picked up his coat and went to the door. “For ten cents I’d ask you out,” he said.

She pouted. Tossed her head, turned abruptly and left the room. Eric watched her leave, wondering, then burst into laughter as she appeared again and tossed him a dime. THE END

When the man in the yellow jeep ahead of her changed lanes, Zemira was possessed with an urge to pursue him. What could possibly be wrong with giving in to her desire?

By Ronni Sandroff | Oct. 1979 | Cosmopolitan

None of the cars were going anywhere. Zemira Kaufman rested her arms on the steering wheel, breathing lightly, determined to cope. She watched a V of Canadian geese move across the white sky. She noted the beauty of the iron train bridge imposed on the whiteness, and the wind fluttering the webbing of the intricate steel towers that rose above industrial New Jersey. Then she resumed the exercises in Fitness for Commuters, flexing, holding, releasing the muscle groups in her body. The delay doesn’t bother me, she told herself. I’m in no hurry.

A horn honked, and she dropped Fitness to the floor of the car, which was littered with other paperbacks she’d bought in her recent zeal to reorganize, rationalize, and stay in command of her life. Become truly self-centered, and you will always find time for others, the books counseled. Zemira didn’t take their advice too seriously, but as she was reading them, she had to admit they had a point. She shifted into drive and moved up behind the yellow jeep she’d been tailing for two hours. The driver of the jeep peered into his side mirror and saluted her. ‘Zemira waved in return. She liked the back of his neck and his vintage jeep. If the traffic stalled long enough, they’d begin to make friends, set up makeshift kitchens, start a new civilization. Zemira watched the traffic closely now. She clung to the back of the yellow jeep, determined to let no one cut in on their budding relationship.

Look how I’ve cut my anxiety level, she thought. If I’d been caught for two hours on the turnpike last month, I might have had a stroke. I’m doing pretty damn good. The autosuggestion recommended in Surviving Urban Horrors had the recommended effect.

Zemira maintained enough alertness to let her car roll along with the rest, but she didn’t indulge in pointless speculations like: “Why me?” or “Why doesn’t the radio report this tie-up?” or “Where the hell are the police when you need them?” Such questions led only to increase discontent and even malignancy, according to the longitudinal research reported in Avoiding Despair: A Cookbook for the Spiritually Rich, also in paperback, also lying on the floor of Zemira’s car along with her flashlight, sparklers, and tire inflators.They were almost off the concrete overpass when the yellow jeep suddenly moved into the center lane. Certainly, the center lane wasn’t going any faster.Zemira stretched across her front seat, rolled down the window, and shouted:”How can you change lanes at a time like this? I’ve been tailing you for two hours. Doesn’t our relationship mean anything to you?”

The driver of the jeep turned around, smiling uncertainly because he couldn’t hear her in the wind.

“You may drive a jeep,” Zemira shouted, “but you have the heart of an eight-cylinder engine.”

He was two car lengths ahead of her, but he shouted back, “It’s a six cylinder.”

Zemira straightened back behind her ‘steering wheel, happy she’d released her feelings. Suppressed emotion thickens the walls of the arteries and causes premature aging. There was no sense bobbing from lane to lane in pursuit of the yellow jeep, was there? Zemira coasted past a truck that said: “It’s Our Pleasure to Serve You.” Past a sedan in which a man and wife were arguing, thoughtlessly depleting each other’s glycogen stores. In the next car, a young man leaned on his steering wheel, quite pale with exhaustion. Then she passed the yellow jeep. The driver had big shoulders and a self-satisfied look which attracted her.

Why shouldn’t she bob from lane to lane if that’s what she wanted to do? She wanted to be behind the yellow jeep. Why let past inhibitions curtail the flow of new behavior patterns?The traffic inched off the concrete overpass. A marshy valley of grass separated them from the oncoming traffic. There was no oncoming traffic. Not a single car, not a van with a sunset spread-eagle on its side, not a bus marked “special.” Imagine an accident large enough to stop traffic in both directions? Maybe a plane crashed onto the highway near Newark Airport. Maybe a meteor fell from the sky.

Zemira turned on the radio again, but the announcer said the winds were so strong their traffic helicopter had been grounded. He recommended an instant printer whose work was so fine it’d bring instant happiness into her life. Instant happiness, indeed. Zemira knew it took at least a half an hour of concentrated work every day. When friends at work teased her about reading self-improvement books, she retorted that they took their spiritual guidance from commercials.

A car in the left lane drove down the marshy hill that divided the highway. Zemira cheered, and the whole line of drivers stuck their heads out their windows to watch. The car got stuck in the mud at the bottom of the embankment, and the heads retreated into their cars.The yellow jeep was ten cars ahead of her in the center lane now. Zemira decided to go after it. She’d cut her losses, cover her bets, get a new deal. Her lane began to move, and she hugged the car in front of her. She passed the truck that thought it a pleasure to serve her, the man still arguing with his wife. The pale young man leaning over his steering wheel hesitated, leaving Zemira just enough room to spin her right fender into his lane behind the yellow jeep.

Both lanes stopped, leaving Zemira’s car at a diagonal between them, but she didn’t care. The man in the yellow jeep shouted for her to listen to her radio. Zemira turned the dial and heard “radio-active waste . . . gasoline fire . . . exits fifteen to seventeen . . . State police are asking-“The crash was so loud it seemed to come from the sky behind her. She snapped her head around, shocked at the sight of an iron rod pulling back out of her broken rear window and then being slammed into her side window. She slipped down in her seat, pulling herself into a knot under the steering column, covering her head with her arms. She heard the iron rod crash through her front windshield. Glass showered and tinkled over her. The shaft of the steering wheel pressed painfully against her neck, but she didn’t move. Rear, side, front windows shattered. She waited for the window on her side to break, wrapping her arms more tightly around her head, controlling her panic with deep, slow breathing.She’d counted twelve breaths when there was a knock on the still intact side window.

“Lady, are you all right?” Zemira put her hand on the seat to pull herself up. Points of glass stuck into her skin. She opened the lock on the door. The wind rattled the glass on the car seat. Arms grasped her shoulders, and she was pulled out of the car by the man in the yellow jeep.

“Are you all right? “He needed a shave. The skin under his neck sagged a little. But his eyes were kind as pine trees. Trust, let go, need others. Zemira leaned against him.

“Did you get cut? Are you hurt?”

She was not steady on her feet, and the wind was strong. The pale young man was being pinned against a car by two drivers. Crowds of people filled the spaces between the cars. Someone took the iron rod, part of a jack, and placed it out of the reach of the pale young man.

“Come sit in my jeep.”

Zemira nodded, and pieces of glass fell from her hair.

“I was hoping to get to meet you,” she murmured. “My name’s Zemira Kaufman.”

He laughed. “A hell of a way.”

“What happened exactly?” Zemira asked, still leaning against him.

“I’ll be glad to be a witness for you, lady. I saw the whole thing through my mirror. I couldn’t believe it. He must be a maniac.”

He led Zemira to his jeep.”My name’s Topler. Peter Topler of Topler’s Lumber Yard,” he pointed off in the distance as if she might be able to see the lumber yard.

Zemira sat in the upright seat, picking glass out of her scalp, examining the ancient dials. “This is a very old jeep.”World War II model. I painted it, changed the engine. . . . Zemira, I cant figure out if you’re in shock or you’re just taking this very well.”

Zemira laughed. “I thought it was a bomb going off. I thought … this is war… now I’ll see if I’m a survivor. I thought, well, I’m glad I’ve been eating a can of sardines from Sicily for lunch every day. Here, feel my skin, would you believe I used to have dry hands?”

Peter Topler felt her skin. “Did you say sardines?”

“The oil helps the skin and also helps you keep calm in emergencies. I mean this has been quite a day. But I guess the best thing to do is stay loose, cut your losses, cover your-“

“Here he comes,” Peter Topler smiled.”Stay loose.”

The pale young, man, escorted by the man and wife who’d been arguing, came up to the ‘indow on Zemira’s side. She turned away. “What about the radioactive waste, Peter?”

Peter picked up the transistor radio from the floor of the jeep and turned on the news. The pale young man tapped on Zemira’s window, gesturing for her to roll it down. Zemira held up one finger, mouthing “wait.” Always allow yourself time to rehearse important confrontations. Peter and Zemira listened to the news spot on the accident. The highway was closed until further notice. Cars would be taken off from the rear by the police. Evacuation of local residents was being considered. Five fire departments were bringing the fire under control.

“It hit an oil truck,” Peter said.

“What did?”

“The truck with radioactive waste.”

Zemira cranked down her window. The cold air hit her along with the whine of the pale young man. “Please lady, don’t report the accident. If I have one more accident, they’re going to take my license away. I have to drive to work. I have high-risk insurance. I’ll pay for the damage, whatever it costs, I’ll pay you.”

“That was no accident,” Peter said, “you deliberately smashed all her windows.”

Zemira sighed. “Not all. I kept waiting for him to break the one on my side. It was the longest wait.”

“Yeah, that’s right, I stopped, I realized what I was doing and stopped. I don’t know what got into me. I never did anything like that before. This traffic, I’m late, I’m supposed to meet somebody.. . . “

Zemira asked the woman who’d been arguing with her husband for a piece of paper and told the young man to write down his name and phone number. Peter nudged her. “Get his plate number, his insurance card.”

Zemira shook her head. “Have you ever read People’s Guerilla Tactics for Beating the Insurance Game? That book says your rates go up with every accident, even if-“

“But what if he doesn’t pay you? He could give you a phony address.”

“I’ll pay, I’ll pay, I don’t want any trouble. I’m going to keep my jack in my trunk from now on. I’m never going to leave my house unless I have to.”

More cars were attempting to cross the marshy divide and get off the highway. The pale young man organized some men to push Zemira’s car onto the grass. Zemira and Peter followed them. She opened the car door and shook the glass out of some paperbacks. She gave the pale young man a copy of Dealing with Anger, Terror, and Other Strong Emotions Without Upsetting Your Enzymes. She hesitated a moment and then handed Love In Today’s Demolition Derby to Peter Topler.

“What are you giving them away for?” Peter asked when they were settled back in his jeep.

“Oh, they’re like disposables,” she said, “the advice only lasts a little while.”

Peter tossed the paperback onto the back seat. “Do you know anything about this radioactive waste? I wonder if we’re going to get sick from it. Or sterile. I’ve never had any kids, have you? None of my marriages lasted that long.”

“How many marriages?”

“Four.”

Zemira nodded. “I think if we eat a lot of sardines and vitamin C, we might be able to cut our losses. I’ll have to read up on it.”

“I don’t feel sick, do you? There doesn’t seem to be anything in the air.”

“You must be burned out on marriage by now.” Peter nodded. “All I want to do is have a good time.”

“That’s a healthy attitude, though in my case I think being married would be a good time. Of course, I don’t know from experience.

“The revolving lights of a police car were visible about twenty cars behind them. Peter stepped out of the jeep and came back to report the troopers were directing cars off the highway. The pale young man drove his car down the marshy divide and got stuck on the bottom.

“We could make it across,” Zemira said, “you have four-wheel drive, don’t you?”

“I think we should stay here. You have to tell the police what happened to your car. I’ll be a witness.”

Zemira touched her hair tentatively, searching for more glass. “I’m going to let him go, Peter.”

“But why? That’s not practical. What if he doesn’t pay for it?”

“Then I’ll pay.” You can’t do that. The guy’s a maniac.You have to turn him in.”

“Look, I can understand. He was frustrated. Stuck in traffic for hours, and then I cut in on him.”

“Zemira, a normal person would’ve honked his horn and shouted curses at you, but no normal person leaps out of his car and smashes someone’s windows.You could’ve been cut to pieces.”

“Who’s to say what’s normal? I sat in my car doing deep breathing for two hours. Is that normal? Some people have a lot of trouble dealing with frustration. I’m thirty-two, and I live at home with my mother who’s probably called the Jersey police six times by now. People at work think I’m some kind of a kook.”

Peter put his hand on her shoulder. “Zemira, that guy was really out of it. He broke your windows and then he just stopped cold and put down the jack and stared out into space. You have to report it.”

“Don’t tell me what to do. It’s my accident.”

“I saw it. It’s my accident too!”

They laughed, bumping foreheads. “I only know you ten minutes, Peter, and we’re having our first fight. I think that’s a good sign.”

“All right, do what you want. But what if you wake up tomorrow and read in the paper that the guy murdered his wife and three kids? How’re’ you going to feel? You’ll be responsible.”

“Oh, that’s an illusion. I can’t control other people. I’m only responsible for myself. Look, I’m very practical. I’ll be inconvenienced for a week while my car is being fixed, but if I start in with the police, I’ll be hearing about this for months, maybe years. Promise you won’t say anything.”

Peter leaned back in his seat, whistling. “You’re a new one on me.”

“And think of that poor young man. He’s going to have to wait down in the ditch for a tow truck. He has to meet someone. I feel sorry for anyone with high-risk insurance. If I had him put in jail, how would he get his car out?”

“I married four women. I thought I hit every type.”

Zemira smiled and held her smile. Bringing Relationships to a Head suggested letting the other person have the last word and punctuating head discussions with a smile.

Peter shifted into reverse as a state trooper directed him into a U-turn. “Where to?”

“Well, first I have to call my mother.”

He nodded. “Do you really think sardines are going to work against radioactivity?”

“It’s worth a try, Peter.”