“You’ll Be Crying in a Minute,” remains one of my favorite pieces. The story was written at a time when motherhood was out of fashion amid all the excitement over women entering and succeeding in the workplace. Those of us who were pioneering working moms got plenty of encouragement for our career advancement, but no acknowledgment for the incredible emotional labor involved in parenting. Although I had a demanding magazine editing job, I always knew that I went to work to rest.

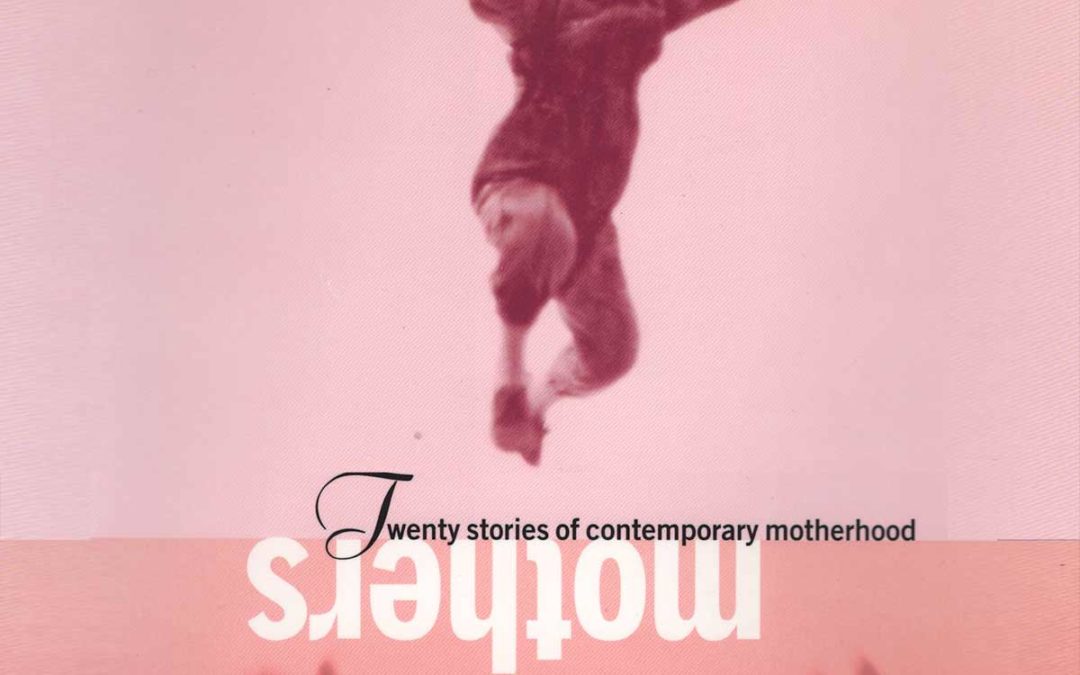

By Ronni Sandroff | 1996 | Mothers: Twenty Stories of Contemporary Motherhood | North Point Press | Originally published in Redbook Magazine

With other people suffering so much anguish, it doesn’t seem fair that the wings of trouble keep passing my family by. The four of us sit at dinner, evening after summer evening, without so much as a cold among us. Our house is not in a flood area, on an earthquake ledge, or near a combat zone: none of us is on methadone, taking fertility pills, or under indictment for a crime. I don’t work at a dead-end job. I have nothing to worry about.

And yet I’m as busy with worry as a woman trying to knit a sweater before her child can outgrow it. Worry knots my fingers; it rubs them raw. I tally all neighborhood suicides and accidents as if I were a bookmaker keeping odds on survival.

I wasn’t always this way. I was so busy tugging at the perimeters of our lives to make them take a shape that pleased me, so busy amending, revising, and adjusting our routines, that I had no idea I’d be filled with dread as soon as everything was right. I was raised to be heroic in times of crisis—to get the children to the hospital emergency room first and faint afterward. I was never taught to handle satisfaction, admiration, praise.

Cara set next to me in the company cafeteria today, and after a comment about hard pears and soggy bread she asked the usual question: “How do you manage both children and a job?”

The next time I give a serious answer to that question, I thought, I’ll have to be paid for it. “Badly—i do it all badly,” I said and tried to turn the talk to the one current film my husband, Gary, and I have managed to see.

“You don’t do it badly,” Cara said. “You just got a promotion—after only three months—and your son and daughter are beautiful.”

I put my sandwich down on its paper plate. Pastrami is hard to chew anyway, but it’s inedible when my mouth is full of motherhood. I tried to be patient with Cara. I admire her long, limp skirts and eyelet blouses, her permanent way, her salad lunches.

“I can’t imagine having kids,” Cara said, her fork darting for an olive. “And I’m almost thirty-three. Neil and I haven’t much time to decide.”

I batted her a few reasons for not having children. I exaggerated Sarah’s aggressiveness (“Almost ever day I get a call from the mother of some child she’s bloodied”) and Kane’s prying (“I think he listens at the door when we make love.”) I told her of the spring of the great chicken-pox epidemic; about going home from our quiet office to find that no one’s put the potatoes in to bake; that Kane needs help with math and, horror of horrors, Sarah has an art project due the next day, and there’s not a shoe box in the house.

Care kept the same bemused expression on her face no matter what I said. “Does it hurt a lot, having a baby?”

“Yes. It hurts a lot, and it keeps on hurting,” I said meanly. Damn her narrow hips and graceful arms. Damn her questions. I don’t want to be forced to make up explanations for what I do with passing, by instinct, blindly. If I’d thought about it as much as she thinks about it, I might have talked myself out of having children too.

The lunch with Cara leaves me shaken. It’s bad luck to hear someone say out loud, as Cara did, that I’ve had more than my share of goodies from life. Something could go wrong at any minute. After I began to work, whole afternoons would go by when I’d forget to worry about the children. I’d try to make it up to them when I got home.

As I drive down our street, I see a white truck with a revolving red light parked near our house. I know it isn’t an ambulance. I know it’s not parked in front of our house. But what if it were? During the one-block drive, I picture both children laid out on stretchers with burns covering ninety per cent of their bodies. There is no place I can touch them without causing pain. Their lungs are scorched; they cry in silence; their eyeballs melt.

The white truck belongs to the electric company. Men are digging in the asphalt in the middle of the street. But even the sight of my family sprawled in front of the huge TV set can’t stop me from completing imagined funeral arrangements for them all. There are rows of sobbing school friends; a grandmother faints at the grave.

The baked potatoes are in the oven. The table is set. The children make a salad while I broil the chops, and although we keep bumping into each other in the small kitchen and green cucumber peels slap the floor, dinner is on the table in twenty minutes.

I sit down in my chair, put my face in my hands, and wait until the anxiety I have felt since lunch can ebb. When I look up, my family is staring at me.

“Hard day?” Gary asks.

“No, not particularly.”

“You look tired,” Sarah says.

Kane wiggles his eyebrows at me, his blue eyes popping in his latest imitation of a TV commercial.

I put sour cream on my baked potato and pour juice for Kane and Sarah. I pass Gary the chops. I tell Sarah not to sit on her feet. I ask Kane to stop wiggling his eyebrows.

The children eat quickly and leave the table before I’ve finished my salad. They go into Kane’s small room, right off the dining alcove, and close the door.

“Remember Kalligan, the man who owned the liquor store on Ocean Avenue?” Gary asks.

I brace myself for a tale of trouble. “What happened to him? Was he hit by a truck? Did he leap from a burning building? Was he arrested for bribing a state liquor inspector?”

“I don’t make these things up.”

“You always bring home terrible news. What happened?”

“I’m not going to tell you if you’re going to take it personally.” But he cannot hold out. “The poor man had a heart attack. He dropped dead in his store. A customer found him.”

“That’s too bad. I liked him.” when will other people say such things about us? Too bad about Sarah and Kane. Too bad about Gary’s accident. Too bad about Sheila’s nervous breakdown—did you hear? They’re giving her shock treatments. She sobs all day, mourning the future victims of a nuclear war.”

I start to laugh, and Gary gives me one of his looks—jaw rigid, eyes cold as aluminum—warning me back to sanity.

“It strikes me as funny sometimes,” I say. I drop a tomato from my fork as I try to explain. “All the world’s problems loom over us like monsters in a nightmare, but we just keep chasing after our personal happiness. The human race is so dumb and funny, and cute.”

Gary smiles tentatively. “Cute, huh?”

“Yes, cut. Especially you.”

We hear thumps and squeals from Kane’s room—the hysterical laughter of a small boy being tickled by his older sister, tickled until his sides ache and he can’t break and wants to put a sneaker in her ribs.

“They’ll be crying in a minute,” I say to Gary. He nods. I rise to rap on the closed door. “Keep the noise down.”

“Okay,” they say, still giggling. I can hear the thumps of pillows being thrown across the room. My mother’s word is struggling to be said: You’ll be crying in a minute. At the most ecstatic moments of my childhood, I heard that.

The laughter turns to shrieks. I try to open Kane’s door, but it is blocked by their bodies piled in a jumble of limbs. I squeeze through the small opening.

“We’re having fun,” Sarah calls.

Kane peers out from beneath her chest and wiggles his eyebrows.

I know someone will get hurt. It’s dangerous to feel so good. Too much happiness attracts the evil eye of disaster. Or is it dwelling on disaster than brings it on? It’s hard to know which superstition to believe. The children, frozen in mid-tickle, start at me. I hold myself tight, refusing to contaminate them with my fears.

“I didn’t’ have the heart to stop them,” I tel Gary, falling back into my chair. “Their idea of fun is to tickle and scream until they turn blue.”

Gary touches my hand. “They’re both at a good age. Not babies anymore but too young to have a driver’s license. Did you hear what happened to the oldest Kenmore boy?”

I smile at him. He’s looking awfully good with his face tanned. I stop wondering why some slim-hipped secretary doesn’t walk off with him; I’ve fed the snapping jaws of worry enough today.

And I resist asking what happened to the Kenmore boy. Our children are at a good age if you can stand the noise, and we’re at a good age too. We’ll all be over the edge soon, but meanwhile, in the sliver of time before the sobbing starts, I let the dangerous feelings of contentment fall like a light shawl on my shoulder and slip off my watch so I won’t be able to count the minutes until the eleven o’clock news.