By Ronni Sandroff | June 1992 | Working Woman

The response was immediate, passionate and overwhelming. Less than a week after the February issue of WORKING WOMAN reached homes and newsstands, thousands of surveys flooded our offices. They came from as far away as Paris and as close as an office building on the next block. Many were accompanied by pages of letters that detailed painful personal experiences. In some workplaces the survey was photocopied and circulated, the results sent back in batches. A man who had been sexually harassed by his female boss wrote that co-workers insisted he fill out the survey. Less than a month after the magazine hit the newsstand, we had received more than 9,000 responses—and they kept coming.

The response was immediate, passionate and overwhelming. Less than a week after the February issue of WORKING WOMAN reached homes and newsstands, thousands of surveys flooded our offices. They came from as far away as Paris and as close as an office building on the next block. Many were accompanied by pages of letters that detailed painful personal experiences. In some workplaces the survey was photocopied and circulated, the results sent back in batches. A man who had been sexually harassed by his female boss wrote that co-workers insisted he fill out the survey. Less than a month after the magazine hit the newsstand, we had received more than 9,000 responses—and they kept coming.

Clearly, the confrontation between Anita Hill and Clarence Thomas had an impact on how and why readers answered. It also had an effect on the human resources executives of the Fortune 500 (the 1,000 companies that make up the top 500 service and 500 industrial corporations). We sent them a simultaneous survey following up a pioneering report “Sexual Harassment in the Fortune 500,” done by this magazine in 1988. This time their responses were somewhat more critical of their companies’ efforts to stop sexual harassment, but, as before, they concluded that the system generally works. Many WORKING WOMAN readers, on the other hand, insist that filing a complaint still amounts to “career suicide.” What’s more, they are angry enough about the spectacle of the Thomas hearings to vote their minds in a year when it matters.

In this, the first major survey to scrutinize and compare the views of these two groups, several messages came through loud and clear:

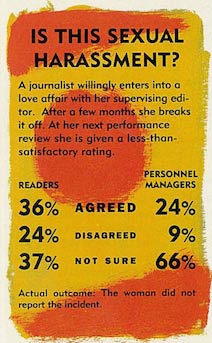

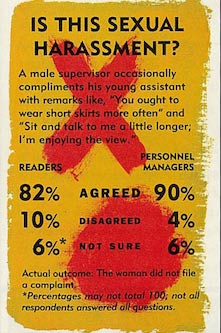

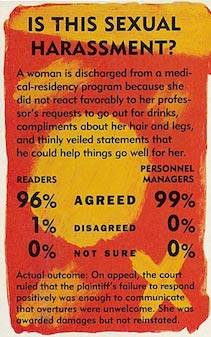

• Women know what harassment is, either by legal definition (54%) or intuition (30%). Only 15 percent were not sure about the boundaries between harassment and harmless fooling around. The 106 human-resources executives who responded go even further than most readers in toeing the party line, but there’s often a discrepancy between what they say is wrong and how they respond to a real situation.

• The higher a woman is in the corporate hierarchy, the more likely she is to be harassed. More than 60 percent of our readers said they personally have been harassed, and more than a third know a co-worker who has been harassed. However, since only one out of four women reported the harassment and most companies receive fewer than five complaints a month, it’s obvious that the vast majority of women who are harassed don’t feel they can safely report a problem.

• Women are not at fault. Provocative dressing and behavior or oversensitivity to sexual jokes is not the cause of sexual harassment, say three out of four readers and most of the personnel officers. And over half of the human resources executives also say that office romances that go sour are not the source of many complaints.

• Women are not at fault. Provocative dressing and behavior or oversensitivity to sexual jokes is not the cause of sexual harassment, say three out of four readers and most of the personnel officers. And over half of the human resources executives also say that office romances that go sour are not the source of many complaints.

• It is an issue that matters. Seventy-five percent of readers feel sexual harassment is an issue on a par with salary inequities, inadequate child care and prejudice against promoting women. And more than 90 percent think their companies and the government can-and must-do more to prevent and stop abuse. Only one out of five women believes that most complaints are given justice, but more than 70 percent of the personnel managers think they are.

• Anita Hill changed the picture. Part of the clarity about this issue must be credited to the national teach-in on sexual harassment during the confirmation hearings for Clarence Thomas last fall [see box]. Fifty-nine percent of readers believe that Anita Hill was telling the truth (compared with only 38 percent of the corporate executives), and more than half the readers and third of the personnel managers plan to vote against their senator if he or she voted to confirm Thomas.

Certainly, the hearings provoked discussion in the workplace. While 37 percent of readers said it was treated as a big joke, almost 40 percent said the confrontation brought the issue out in the open and led women to trade war stories about sexual harassment. Here’s what they said.

WHO GETS HARASSED?

The old prey on the young, and the powerful on the less powerful. A female subordinate under 34 being harassed by a male over 35 is the most common scenario, according to both readers and human-resources executives. Almost 30 percent of the incidents occur when the women are 18 to 24 years old-a very large number, considering the small size of this age group in the workforce. In 83 percent of the cases, the harasser is in a more powerful position than the harassed. ” [As] the youngest and newest nurse in the department, I was eager to please,” writes a reader in Hawaii who was harassed by her supervising doctor. “At first [his] remarks were mildly flirtatious. Later he began to be more bold. The one time I was ever alone with him, he grabbed me and kissed me. The last straw was when he, I and another nurse were in our lab. He casually asked how old I was and [said], ‘I wouldn’t want to f—you because it would be like f—ing one of my daughters.”‘

Harassment becomes much more common when women enter some predominantly male workplaces or breach the formerly all-male domain of upper management. “The higher up you climb, the worse the harassment gets,” writes an insurance-company executive from Iowa. “Men feel threatened and choose this behavior to deter our advancement.” Women in managerial and professional positions and earning over $50,000, as well as those working in male-dominated companies, are more likely to experience harassment.

That’s probably why WORKING WOMAN readers reported higher rates of harassment (60%) than respondents to other surveys, whose rates hover between 25 and 40 percent. Lynn Hecht Schafran of the National Organization for Women’s Legal Defense and Education Fund says the WORKING WOMAN figures are “not out of line with what we see in surveys of professional women.”

Recent polls of female chemical engineers, lawyers and executives also found that roughly 6 out of 10 women report harassment. “[I have been] patted, poked and squeezed to death at industry meetings,” writes a marketing executive who worked for a Fortune 500 chemical company. “When I was in sales, I was one of only two females in a division of 22. At regional meetings, the guys always went to strip joints. I [went] back to my room.”

The incidents that reach the attention of corporate officers are often severe, and the profile today is even worse than the one reported by Fortune 500 executives in 1988. Pressure for dates and/or sexual favors occurred in 50 percent of the cases reported to company executives this year but in only 29 percent of the cases in the 1988 survey. In 1992 over 34 percent of the reported incidents involved touching or cornering, compared with 26 percent in 1988. And most of today’s complaints are valid, according to 68 percent of the executives surveyed-4 percent more than agreed with that statement in 1988.

WHY DO MEN DO IT?

It’s not flirtatiousness, hormones or sexual desire, say many readers. The desire to bully and humiliate women is behind most harassment, according to one out of two readers. “The harasser wants a victim, not a playmate, and a woman with modest dress, makeup and comportment are just as likely-maybe even more likely-to be harassed,” writes a Washington professor.

It’s not flirtatiousness, hormones or sexual desire, say many readers. The desire to bully and humiliate women is behind most harassment, according to one out of two readers. “The harasser wants a victim, not a playmate, and a woman with modest dress, makeup and comportment are just as likely-maybe even more likely-to be harassed,” writes a Washington professor.

A relative few may be responsible for a hefty percentage of harassment cases. Forty-seven percent of the readers who have been harassed have known “chronic harassers,” men who bully one woman after another at work. “Most [harassers] share a common goal-intimidation,” writes a 29-year-old secretary from Pennsylvania. “If someone is capable of harassing a co-worker or subordinate, they’re also likely to take advantage of people in other ways.” Her insight is confirmed by Freada Klein, who conducts training sessions on the problem for major corporations. “We’ve found that workplaces with high rates of sexual harassment also have high rates of racial harassment, discrimination, and other forms of unfair treatment.”

IF IT HAPPENS TO YOU

When asked what they would advise a close friend or relative to do if she were being sexually harassed at work, 79 percent of readers took an assertive stand: “Let the perpetrator know, loud and clear, that if the behavior doesn’t stop, she will turn him in,” one respondent replied. But their advice is often a case of “Do as I say, not as I do.” Among those who themselves have been harassed, only 40 percent told the harasser to stop, and just 26 percent reported the harassment.

Women are not unaware of the contradiction. Though a public-relations director from Houston advises others to fight back, she admits, “I cannot say absolutely that I would file charges, because I need that job! And that fact makes me really angry.”

Trying to ignore the problem was the most common tactic (46%). “A disapproving look or turning away is an almost pitiful strategy for a woman to sympathize.” In fact, a firm “No” can work better than ignoring the problem. One out of three women who protested got the harasser to stop, compared with one out of four who tried to ignore or avoid the harasser.

Dr. Rita R. Newman, a psychiatrist and former president of the American Medical Women’s Association, advises women to document harassment-in dated, written notes or on cassette or videotape even if they don’t intend to report it. If the situation later escalates and you’re forced to take action, you have contemporaneous documentation, which is looked on quite favorably by the law. Even if you never report the incident, Newman says, gaining some control over the situation through documentation can help preserve self-esteem.

CALCULATING THE DAMAGE

Sexual harassment clearly does hurt women, whether or not they go through the often grueling process of filing a complaint. Readers who were harassed reported such ill effects as being fired or forced to quit their jobs (25%), seriously undermined self-confidence (27%), impaired health (12%) and long-term career damage (13%). Only 17 percent reported no ill effects.

Sexual harassment clearly does hurt women, whether or not they go through the often grueling process of filing a complaint. Readers who were harassed reported such ill effects as being fired or forced to quit their jobs (25%), seriously undermined self-confidence (27%), impaired health (12%) and long-term career damage (13%). Only 17 percent reported no ill effects.

Health problems associated with harassment are similar to those that spring from other stressful situations, such as headache, chronic fatigue, nausea, sleep and appetite disturbances and more frequent colds and urinary-tract infections, says Dr. Diane K. Shrier, professor of clinical psychiatry and pediatrics at New Jersey Medical School at Newark. “Often women and their doctors don’t recognize any links between these symptoms and harassment. And yet, when you take a careful history, you’ll see that the symptoms began as harassment occurred and begin to go away once the situation is resolved.”

Emotional turmoil, which usually affects work performance, is also common. “Women may feel that unless they go along with the harasser, they will face the end of their professional lives,” says Newman. “So they feel exploited, cheapened and forced to submit. For some, self-esteem is impaired forever.”

Forced career detours also take their toll on women’s earning power. “I lost or was forced out of my job each time, while my respective harassers are busily laying, tormenting, embarrassing or firing people as we speak,” wrote a former personnel coordinator from Illinois who was harassed on three different jobs over a long career. The harassed may be doubly victimized by being blamed for the results of their harassment. Many readers who complained were told to take a course in “how to deal with difficult people” or given poor marks on their next reviews.

THE ODDS OF GETTING EVEN

If a woman does decide to fight back and report harassment, what are her chances of getting justice? That depends quite a bit on whom you ask. Those who write company policies are much more bullish about how well they work than those who must use them. Only 21 percent of readers agree that complaints are dealt with justly, and over 60 percent say charges are completely ignored, or offenders are given only token reprimands. Fifty-five percent who have tried reporting harassment found that nothing happened to the harasser. “For 19 years I have been in the Air Force,” writes an information-systems manager. “I have been humiliated by everything from males throwing me up against a wall, running hands up my skirt and grabbing my breasts to sexist jokes and nude pictures plastered over my work station. A year ago a major [showed up at] my house at 10:30 PM. (Fortunately, both of my sons are over six feet.) At work [the major] was always humiliating me by ordering me to straddle the arms of a chair in my skirt and by . rubbing his hands up and down my back and sides. [When I complained], I was threatened to stop pursuing my EOT/EEO complaint, ‘or else.’ I was told that because the major outranked me, his word carried more truth than mine.”

The executives responsible for hearing complaints believe a just resolution is much more common; over 80 percent say most offenders in their companies are punished justly. But that number is down from the1988 survey; then 90 percent of the executives believed offenders were justly punished.

“this is the key contradiction in sexual harassment in the 1990s,” says Freada Klein, who analyzed WORKING WOMAN’S 1988 survey. “In every workplace, we’ve surveyed, we find that a majority of employees don’t have faith in corporate channels for complaint.”

Today 81 percent of Fortune 500 companies report having training programs on sexual harassment compared with only 60 percent in the 1988 survey —although only half of WORKING WOMAN readers work for a company with these procedures.

Most Fortune 500 executives believe their own companies are doing a good job in this area. Even if they are, women believe government must help bring about real change. Most think it should ease (78%) and speed up (80%) the complaint-resolution process, increase the 6-10-month (depending on the state) statue of limitations for reporting abuses (60%) and increase penalties for companies (66%).

THE ULTIMATE INFLUENCE

More and more, the power of the purse will promote change. Interestingly, Fortune 500 executives see their companies as much more legally vulnerable than do readers. The 1991 Civil Rights Act gives harassment victims the right to a jury trail and compensatory and punitive damages for financial and emotional harm, with awards based on company size. Congress is expected to pass an amendment that would lift the current cap ($300,000) on these awards, but companies fear that even with limits, sexual-harassment suits will become the “next asbestos.” it may cost Corporate American more than $1 billion over the next five years to settle these lawsuits, according to calculations by Treasury, a magazine for financial executives. Many companies may begin to push the burden onto the harassers—by firing them promptly.

Even in that legendary lair of harassment, the construction site, fear of monetary loss can bring about change. A female architect, 39, from Chicago reports that one contractor deals with complaints against harassers by immediate dismissal, no reassignment, no second chance. Walking through the job site is like walking through an altar boy’s convention. The color green is the most powerful motivation in this country.”

Behavior can turn around quickly in a workplace once the stakes are raised high enough. “Economic and legal pressures may not immediately change attitudes—that can take decades—but they can change behavior,” notes Helen Neuborne, executive director of the NOW legal Defense and Education Fund. And changing behavior is good enough.

Ronni Sandroff won a Page One Award for her 1988 story “Sexual Harassment in the Fortune 500,’ in WORKING WOMAN.